Help

What is a Footprint?

Welcome to Footprints: Jewish Books Through Time and Place!

Footprints is a project that researches the the movement of books as material objects. Following specific movement will allow us to learn about the wider, collective, impact of printed matter. The “footprint” concept is a tool we have developed that allows us to trace this movement.[1]

1) The building block of the database is the individual footprint. A footprint is the reconstruction by the researcher of a moment in time when we can place a book-copy in a particular place and/or with a particular person (an owner, a librarian, someone seeing the book, a giver, a subscriber, a censor [expurgator], etc.).

- a) Some footprints will have a lot of information: a specific time, a specific place, a named person with a named role.

- b) Some footprints will be less complete: you might have an owner’s signature in a book-copy. But you might not know the exact date (or range of dates) that the book came into the owner’s possession or where the owner possessed the book.

- c) So a “footprint” can be entered into the database with whatever information you have that locates the book-copy in place and time and whatever information you have that connects the book-copy to a specific person or persons.

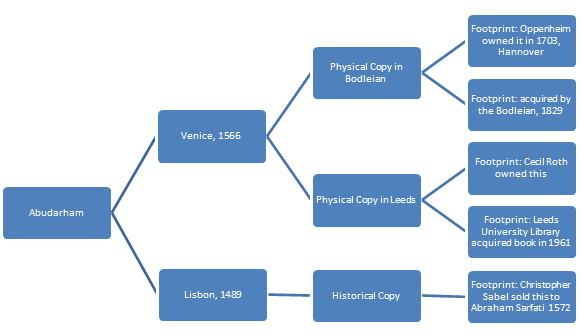

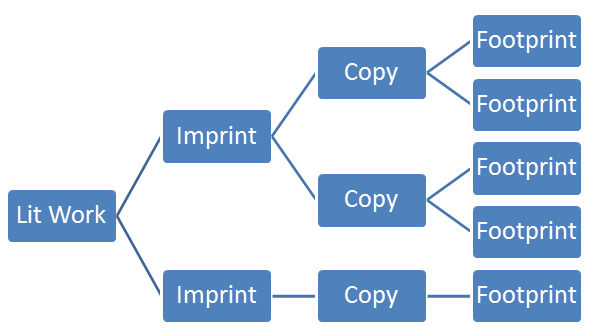

2) The second key thing to understand is the different kinds of vocabulary that we use for the “books” we are studying. We have 3 basic levels (exemplified below using: the Abudarham footprint)[2]:

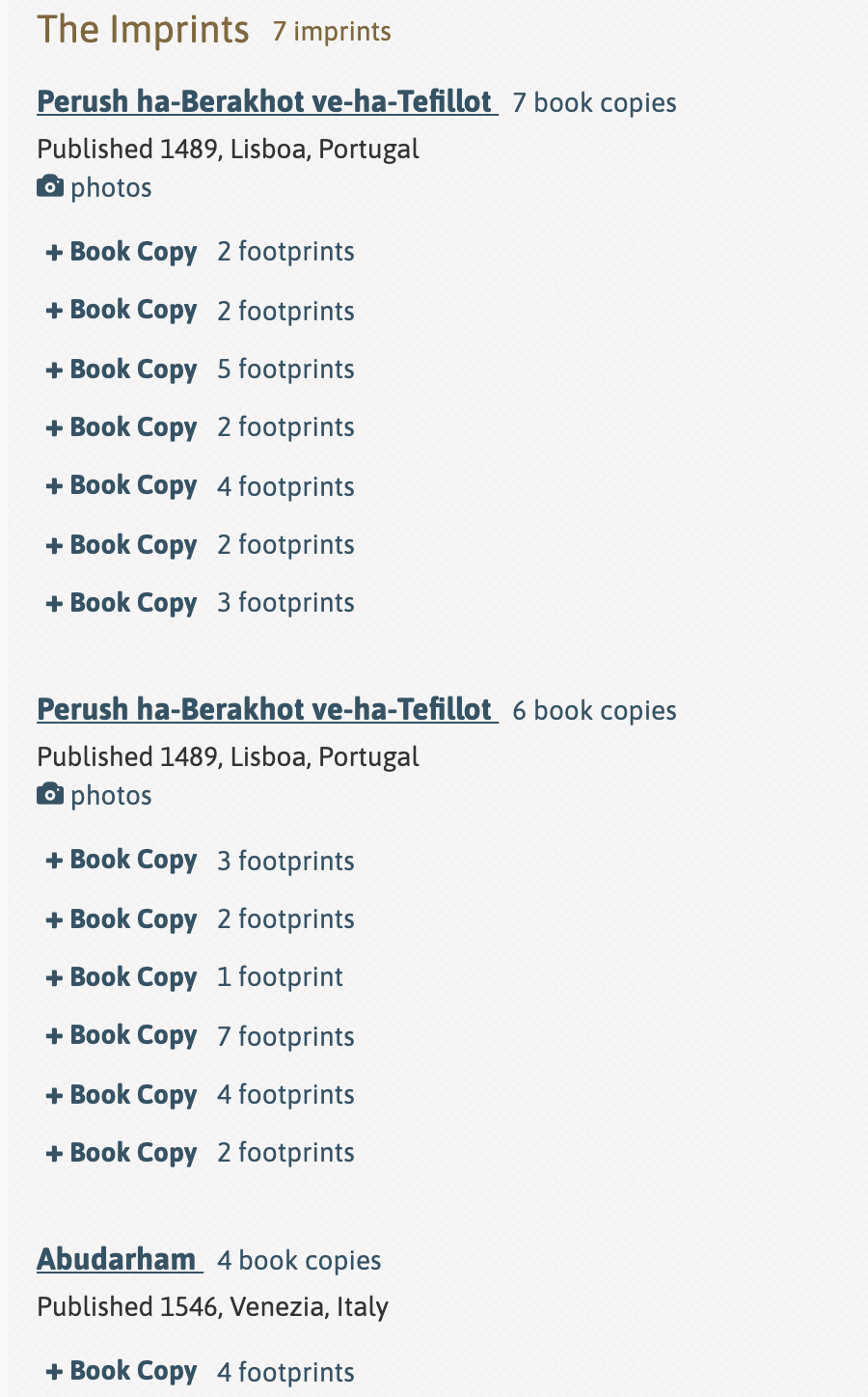

- a) At the top is the “literary work,” ie, a title, such as the Abudarham, a commentary on synagogue liturgy, by a 14th-century Spanish rabbi, David ben Joseph Abudarham (or Abudirham).

- b) At the next level is the “imprint,” or edition, -- e.g. the printing of Abudarham at the Cavalli press in Venice, 1566.

- c) At the next level is the “book copy” (or just “copy”): this is a specific copy of a particular imprint/edition. We have two types of copies that we deal with:

- i) an extant or “physical copy”: this is a copy whose whereabouts are known (e.g. a copy of the 1566 printing of Abudarham in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, Shelfmark Opp. 4o. 457)

- ii) a “historical copy”: this is a copy that we know about from a historical source (an estate inventory, an old library catalogue, correspondence, an incidental mention, an auction or bookseller’s catalogue) but whose whereabouts are not known to us today. An example of this is a copy of the Abudarham (imprint not certain but likely that 1566 printing) known to have been owned by a woman named Rachel in Cunico, Italy in 1572.

“Footprints” are of copies of imprints of literary works. Any one copy can (and usually will) have multiple footprints. Each time a copy moves or changes hands or is connected to a particular person or place, it will have a new footprint.

Remember that footprints are generated by the researcher. They are historical conclusions based on material evidence from the past. (Just like any historical conclusion, in fact.) It might be helpful to think about it this way:

Concrete Examples (or skip to the step-by-step instructions below): Spend some time in the database browsing the footprints (showing various imprints and physical and historical copies).

Start here, with a footprint for the Abudarham:

The option on the right, “view all footprints for this literary work”

Should take you to the written work page here:

This page has a lot of options for each imprint and each book copy to expand or hide the individual book copies and their associated footprints.

Also notice the URL’s: each footprint has a number which will show up in the URL. So does each literary work. Each imprint has a number which shows up in a URL along with the literary work.

Evidence

Footprints is a scholarly project, which means that we show our work in order to persuade other users of the veracity of our claims. A number of fields in the entry for each footprint deal with the evidence that establishes the footprint. More on this later, but for now, it’s important to think of this as the footnote to the footprint (read that again, out loud). This is the source that gives us the footprint. Of course, in many cases, what will give you the footprint will be multiple sources (as in most kinds of scholarship). The evidence is the starting point of your interpretation. (Other types of sources will be mentioned by you in the notes field.) For example, you might be looking at a book-copy with a censor’s signature and a date. That book-copy is your evidence. But to reconstruct where that censor was working in that year (to figure out the place for the footprint), you will probably need to look at William Popper’s appendix to his book on censorship (which we’ve compiled into a handy chart, here). Your evidence is the censor’s signature in the extant (physical) copy. But Popper deserves a citation in your notes field--a simple Chicago-style note suffices.

Another example: you are looking at a library inventory from the 18th century which lists a particular book. You happen to know that the book is still in the library at a particular shelf mark and with a nice catalog entry in the libraries’ 21st-century digital catalog. Your evidence is the 18th-century inventory. But you will also provide the URL of the digital catalog entry in your notes.

We have a handy guide to types of evidence and which fields to use to describe the evidence here.

[1] Generally we use “Footprints” (initial cap, italics) to refer to the project and the database. Lower-case “footprint” refers to the building blocks of the database.

[2] Technical Point: We use a “modified FRBR” system: Literary Work=Work + Expression Imprint=Manifestation Copy=Item Footprint (one step beyond the traditional FRBR system)